Will AI Replace Us? The Role of LLMs in Writing and Coding

Introduction

The emergence of ChatGPT in 2022 and the widespread use of intelligent chat bots have increased the popularity of Language Models (LM) [1], these Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems have not only transformed how we communicate but also have started to change key sectors including research, education software development and the arts [2]. Moreover, their ability to generate and understand human text has opened up new opportunities for development of automation and creativity across disciplines [2, 3].

The integration of LMs into these worlds, however, has brought a series of trials and ethical issues that are not just technical [4]. In research writing, for instance, LLMs are being used to help compose papers [2]. This has prompted questions concerning facile authorship, authenticity, and whether these AI systems must be made responsible for revising scientific manuscripts instead of human reviewers. Meanwhile, software engineering tools like GitHub Copilot [5] allow coding in a natural language to be translated into machine code, but they also introduce concerns regarding privacy, cybersecurity, and reliance on these automated tools.

The creative industries also are experiencing a similar issue, on the one hand, LMs can collaborate with artists and writers to generate new of literature, music and visual art. While, parallel to research writing, the widespread use of these technologies in creative sectors raises questions about where the limits of creativity and authenticity lie. Who is truly developing new art-the human or the machine? If the latter, can such content be considered original? These concerns are amplified by the fact that LMs are trained using vast datasets, including works by renowned authors.

This essay seeks to delve into these debates to discuss the role of current LMs in our society and whether, as automated tools, they might eventually replace us in the near future, especially in the contexts of research and software development. By analyzing both the opportunities and the risks associated with LLMs, it aims to analysis how these models are shaping the future of knowledge creation, technological innovation, and creative expression. Consequently, this report is organized as follows. First, Section 2 explains what LMs are from a technical perspective, why they have been a breakthrough in recent years, and whether they have the potential to replace us in the future. Second, Section 3 discusses how LMs have impacted academic writing and its ethical debates. Third, in Section 4, it explores the adoption of LMs in the software engineering industry and their potential to replace programmers. Finally, in Section 5, I provide final insights on these questions and discuss what we can expect from the future development of AI in these areas.

AI and Large Language Models

The ability to master human language have been always a goal in Computer Sciences. In 1950, Alan Turing developed his famous "Turing Test" [6], which determines whether machines can hold a conversation with human users without the users realizing they are interacting with a machine. More than ever, the Turing Test continues to challenge the boundaries of computer science and artificial intelligence.

In 1964, Joseph Weizenbaum from MIT introduced ELIZA [7], one of the first conversational agents in the history of Computer Science and AI. ELIZA sought to simulate a psychotherapist by using a set of logical rules to interact with human users, giving the illusion of text understanding even though it was simply responding to certain word patterns with predefined rules. While, in the 1950s, Claude Shannon pioneered statistical and predictive modeling of written language [8]. Using information theory, he measured the difficulty of predicting words based on previous context in a text corpus, laying the groundwork for later statistical language models. However, in 1957, linguist Noam Chomsky criticized the limitations of purely statistical models for capturing the complexities of human grammar [9]. To demonstrate this, he presented two invented sentences: "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" and "Furiously sleep ideas green colorless". Chomsky argued that even though both lack of semantic meaning, just the first one it is syntactically correct, but the statistical LMs study by Shannon would consider both sentences equably plausible.

The development of LMs can be divided into three phases, which I will explain in the following subsections:

Statistical Language Models

In 1990, there was a significant breakthrough in how language was processed by computer systems, introducing the idea of using probabilities to compute the likelihood of each possible sentence from a finite set of words [10]. For example, the following sentences:

- The dog barks.

- A bird flies to the ground.

Both of these sentences are syntactically correct because they follow the rules of the English language, but only the first one is semantically correct. It is common knowledge that dogs are able to bark, but it does not make sense that birds fly to the ground instead of the sky. Consequently, it is expected that a language model could assign a higher probability to the first sentence.

From a mathematical perspective, each word, w, is treated as a random discrete variable from a finite set of words called the vocabulary. Therefore, the model can assign a probability to any possible sentence:

$$ p(s) = p(w_1, w_2, ..., w_n) $$

This formula can be converted to this using mathematical properties and compute all of the probability related to a given sentence $w_1, w_2, ..., w_n$:

$$ p(w_1, w_2, ..., w_n) = p(w_1) \times p(w_2|w_1) \times p(w_3|w_2,w_1) \times ... \times p(w_n|w_1, ..., w_{n-1})$$

However, computing the probabilities of this formula can be really computationally expensive when a long sentence is found in a corpus of text. To address this limitation, researchers have used the Markov assumption, which restricts the amount of memory of previous words needed to predict the next word. Reducing the formula to this:

$$p(w_1, w_2, ..., w_n) = p(w_1) \times p(w_2|w_1) \times p(w_3|w_2) \times ... \times p(w_n|w_{n-1})$$

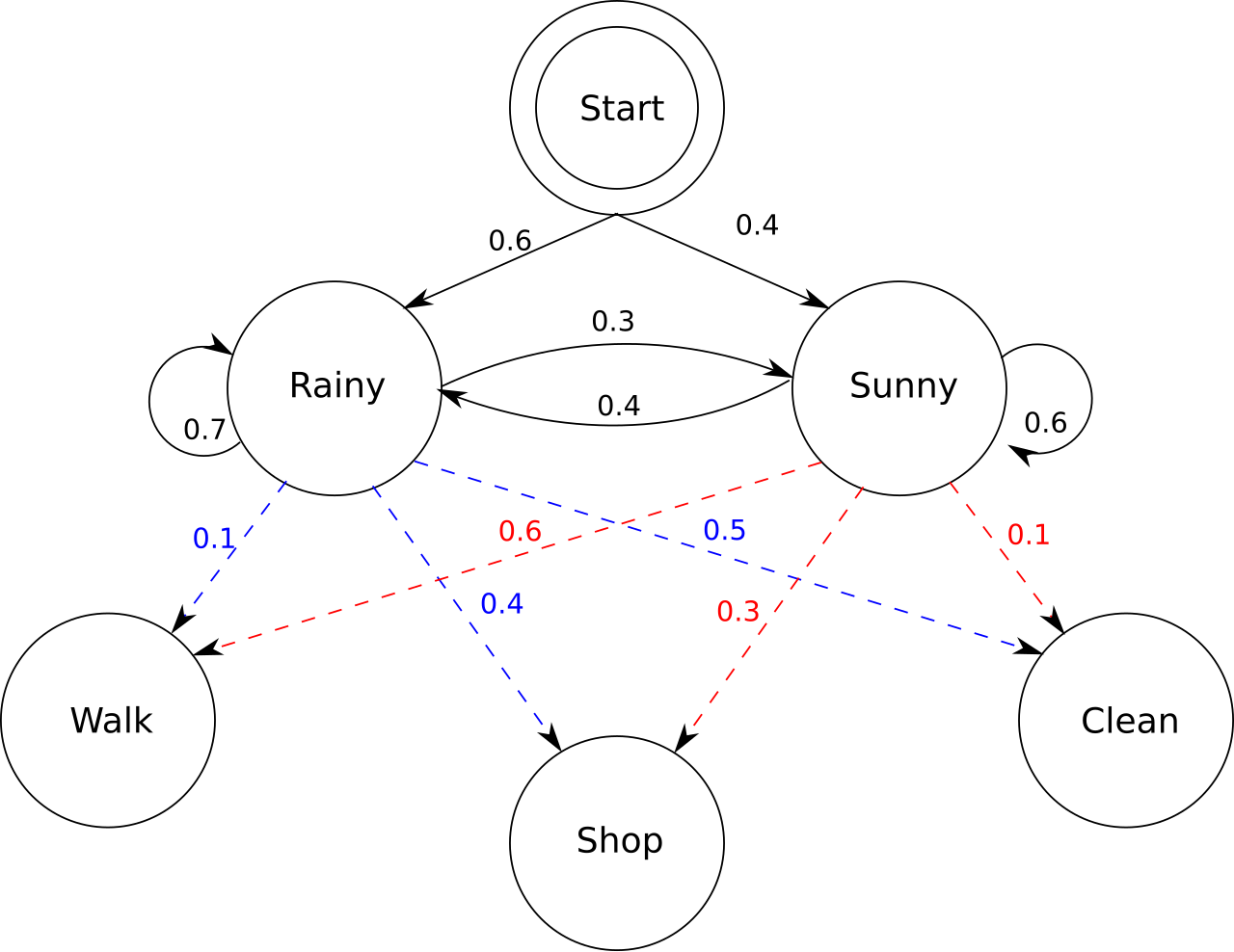

With these changes, processing and training statistical language models become more tractable using computer resources. In Figure is possible to visualize how probability can be scored. However, these models present several limitations, including difficulty in processing long contexts and an inability to detect similar textual contexts.

Neural Language Models

Neural Language Models (NLMs) [11] introduce a paradigm shift against stadistical LMs to face their limitation such issues to process long sentences and long texual contexts. These models learn distributed representations of words (called word embeddings [12]) and predict the probability distribution of the next word in a sequence of words or sentence. Unlike statistical LMs that rely on explicit counts of word combinations, NLMs learn latent features and capture patterns from from data.

Word Embeddings

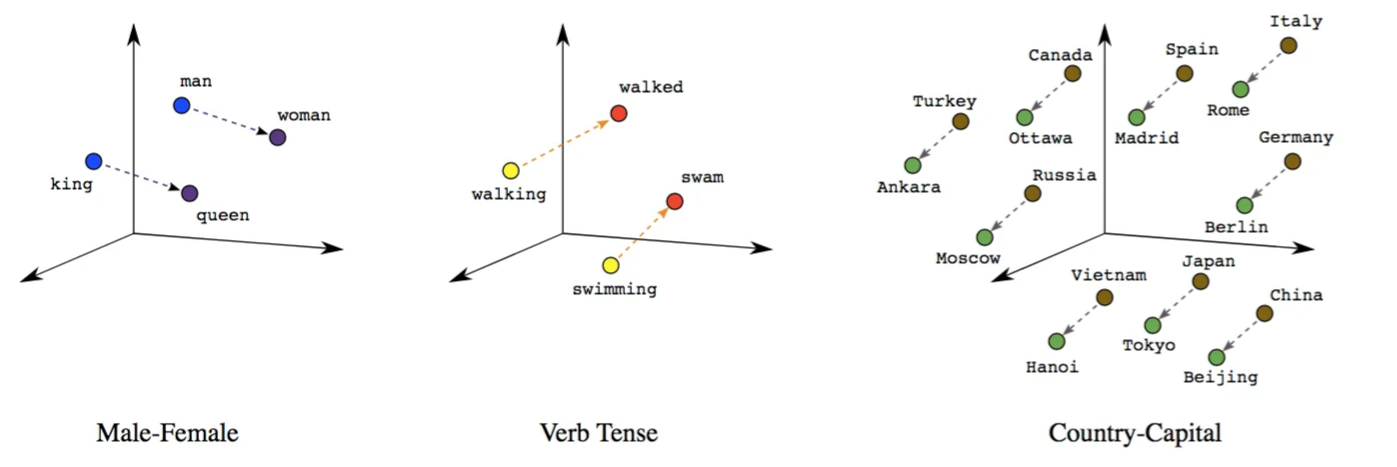

Word embeddings are dense, low-dimensional vector representations of words that capture semantic (meaning-based) and syntactic (grammar-based) relationships [12]. Consequently, these model map words to continuous vectors where similar words are closer in the vector space.

The benefit of this approach is that the vector space, based on the vocabulary of the text corpus, allows us to mathematically measure whether two words are similar using properties such as distance functions, including cosine similarity. For example, the figure shows that the word vectors capture both syntactic and semantic similarities in the language.

However, Word Embeddings present two important limitations, which are:

- Word Embeddings are static vector representation that assign the same vector to a word regardless of its context, conflating multiple meanings (polysemy). For example, the word bank can be used in language as bank institution, but at the same time as river edge.

- Word Embeddings struggle to handle rare words or Out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words (words not seen during training get random vectors), assigning not good representations to these words.

Recurrent Neural Networks in Language Modeling

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are a specialized type of neural network designed to process sequential data, such as text, where the order of elements is crucial [13]. In language modeling, RNNs are used to predict the probability of the next word or character in a sequence, given the preceding context.

RNNs maintain a hidden state that acts as memory, capturing information from previous time steps. At each step, the RNN takes the current input (e.g., a word or character) and the previous hidden state to produce a new hidden state and an output. This allows the network to "remember" past information and use it to inform future predictions. On the other hand, RNNs mitigate Word Embeddings limitation using character-level or sub-word units to build word representations from smaller, shared components allowing to learn different representations with words that have several meaning based on the context.

Although NLMs represent an advancement over statistical language models, these models could only address one task per architecture, and were not capable of generalizing to other tasks, unless the approach or the architecture, for which the model was initially designed was changed.

Pre-trained Language Models

One limitation with NLMs and with neural network-based models in general is that they require a massive amount of data to achieve good performance on NLP tasks, including sentiment classification, text summarization, or question answering. However, the specific task that LMs face is to predict the next word in a sentence given the previous ones; this approach is based on the distributional hypothesis. For example, in the sentence ``I have a gift for my ...'', an LM must determine which word is plausible according to the probabilities of the words in the vocabulary and the context.

According to the task of predicting the word in sentence Peters et al. in 2018 advanced this idea to the next level and propose ELMO [14]. ELMO is a LMs based on recurrent neural networks trained on massive corpus of text. The main idea of ELMo, unlike other models based on recurrent neural networks, was to leverage the knowledge acquired from vector representations of text to predict the next word in a sentence, which proposes a paradigm shift by using not only the previous words and context to predict the next word, but also the knowledge acquired by the model during its training phase. While this achievement surpassed several state-of-the-art models at the time, ELMo required processing each word in a sentence sequentially, which did not allow for parallelization of this task and made training for scalability with larger datasets more difficult.

To address these challenges, Vaswani et al. [15] in 2017 introduced a new neural network architecture called the Transformer, based on the attention mechanism, which enables parallel processing of text sequences. This makes them particularly well-suited for execution on specialized hardware such as GPUs and TPUs, which, in turn, makes them highly parallelizable. These achievements paved the way for the introduction of pre-trained language models [16], which were no longer trained from scratch but were instead pre-trained on the language modeling task. This knowledge could then be leveraged for more specific tasks, such as sentiment classification.

Companies like OpenAI leverage these advances to scale and develop their own Transformer-based models, known as Generative Pretrained Transformers (GPT) [17]. This series includes GPT-1, GPT-2, and GPT-3, each with a larger parameter size than its predecessor. However, the most notable aspect of these models is the emergent properties that manifested as parameter size increased. These properties open a difficult debate among the academic community about whether these emergent properties truly represent context-based learning, or if they are simply a manifestation of the extensive training corpus that contain relevant information for each existing tasks in the SOTA.

The emergent properties in LMs [18], now called Large LMs due to the vast number of parameters in their neural-based architectures, have allowed them to solve a wide range of tasks, such as question answering or mathematical problems, as long as these tasks can be expressed in text. This capability has given rise to what is now known as Prompt Engineering.

All these advancements have converged in what we now know as the generative capabilities of LLMs (the ability to generate text at a human level) [19], which have sparked extensive debates about whether these AI systems will replace us in the near future.

Role of LLMs in Research Writing

In March 2024, a tweet made viral in social media regarding a paper published in the academic journal Elsevier’s Surfaces and Interfaces because its introduction started with the following sentence: "Certainly, here is a possible introduction for your topic", which is a typical answer from ChatGPT to user questions. LLMs such as ChatGPT and others have been increasingly used to assist academic writing, showing rapid adoption in computer science papers. For example, Zou et al. [20] found that 17.5% of computer science papers and 16.9% of peer review text had at least some content drafted by AI. The paper on LLM usage in peer reviews will be presented at the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICLM). To illustrate these findings, Zou et al. [21] highlight specific words such as commendable, innovative, meticulous, pivotal, intricate, realm, and showcasing which are more commonly used in ChatGPT-generated answers than in human writing, by comparing several papers published before and after the release of ChatGPT.

This has become a problem for journals and scientific conferences, as they do not know how to manage the use of AI tools. Some journals have forbidden their use in calls for papers, while others have allowed their use as long as authors explicitly state their use in the contributions of each author. However, the big question is: is the use of AI tools for improving academic writing an ethics violation? On the one hand, since most research literature is written primarily in English, using these tools can help facilitate and level the playing field for researchers who are not native English speakers. On the other hand, LLMs have been trained on large data repositories, often without proper concern for copyright, raising questions about the originality of the content generated when using LLMs in scientific writing. Furthermore, a question that the scientific community has been asking is whether LLMs are capable of demonstrating basic reasoning abilities. What would happen if LLMs were scaled even further, made even larger? Would they achieve higher levels of reasoning, or are these models simply capturing statistical patterns, generating the most likely outputs based on internal probabilities?

From the perspective of the author of this article, LLMs fall into the latter category, tools that can very effectively mimic human patterns at scale. This would imply that these models can learn to imitate, but not to generate new knowledge. Can we entrust the development of science to such an AI? Clearly not. Even more so, can we trust it with the dissemination of science? A resounding no. Therefore, scientific research must still be carried out by humans, especially its dissemination through academic writing.

Another topic that has been widely debated in the scientific community is the use of LLMs for reviewing scientific articles [22]. Should these models be used instead of the traditional peer review process in journals and scientific conferences? A major issue in academia is that researchers are often very busy working on their own research, leaving them with little time to focus on tasks unrelated to their main projects. As a result, the use of LLMs has become widespread among researchers for reviewing scientific papers. However, as mentioned earlier, LLMs are not capable of identifying the gaps that a paper might have, making human review by an expert in the field essential. Furthermore, many LLMs are general-purpose, while reviewing scientific articles requires a high level of specialization that LLMs often lack within their internal knowledge.

However, from my perspective as the author of this article, I do agree with the use of LLMs as complementary tools that facilitate the research process. For example, using LLMs to help correct the English grammar of non-native speakers, or to summarize papers to make them easier to read. Furthermore, some articles can be difficult to understand when the reader is not an expert in the field. The use of LLMs can help mitigate this by making such papers more accessible and by suggesting new directions for current research. Furthermore, during the article review process, in the opinion of this author, LLMs can also assist reviewers by pointing out potential aspects that might be overlooked. However, under no circumstances should they replace researchers in the traditional peer review process.

Coding and Software Development

LLMs have transformed the way software engineering is carried out across different development teams, bringing several technical strengths and benefits that improve productivity and code quality [23]. For example, the generative properties of LLMs excel at improving code generation and automating documentation tasks. Consequently, developers have started to use these tools as part of their daily work, among the technical benefits that LLMs have brought:

- Code Generation: LLMs like GitHub Copilot, equipped with OpenAI's Codex, enable developers to generate code from natural language descriptions, which speeds up coding and reduces repetitive tasks. This increases productivity by automating routine activities such as writing code and implementing algorithms. Furthermore, LLMs offer cross-language support, allowing developers to work across multiple programming languages without needing to master each one and opening up access to write code from multiple programming languages using just one tool.

- Code review and Debugging: LLMs are used to automate code reviews and assist with bug detection, changing the software development process and enhancing code quality. For example, models such as ChatGPT can analyze code for errors, suggest improvements, and help junior developers perform effective code reviews by leveraging best practices. Traditionally, debugging is a manual process, but LLMs can analyze logs, error messages, and suggest potential fixes. This capability is especially valuable in large systems, where bugs are difficult to track down and fix.

- Refactoring: As software systems grow, they accumulate technical debt, which makes software systems difficult to maintain in the long-term and might affect their performance in the future. LLMs can help by identifying code that needs refactoring, suggesting simplifications and eliminating unnecessary code. They also recommend more efficient algorithms and design patterns, and provide insights into performance issues such as inefficient loops or memory usage.

- Documentation: Keeping software documentation accurate is challenging and time-consuming, but its importance for maintainability and collaboration is one of the most important parts of software development workflow. LLMs can automatically generate and update documentation by analyzing code, explaining functions, classes, and modules. This keeps documentation aligned with code changes and helps developers understand complex, especially in agile environments where requirements frequently change.

These are some of the main technical benefits that current LLMs have brought to software development teams. However, these benefits have also raised a series of concerns among researchers and tech leads regarding the use of LLMs by developers and software engineering teams. Which from a technical perspective LLMs are far from being perfect, for example of them limitation that they have:

- Lack of code comprehension: LLMs lack human-like comprehension of code, they rely on statistical and probabilities patterns to predict sequences rather than understanding underlying the intent. This poses challenges in software engineering, where code must align with business requirements and software best practices. For example, an LLM might generate a syntactically correct sorting algorithm but overlook implicit efficiency needs like time complexity. Consequently, while LLMs aid in generating code snippets, their outputs require human review to ensure they meet functional and non-functional system requirements.

- Inability to handle rare issues: LLMs like GitHub Copilot are really good at learning patterns from vast text information, which means they perform best when tasked with solving common or well-documented problems. However, when faced with problems that are not present in their training data, LLMs struggle to find effective solutions or generate meaningful answers for novel issues that arise from changing client requirements or project specifications in software engineering.

- Computational resources: LLMs require a lot of computational resources for both training and inference, usually this rely on large clusters of GPUs or TPUs, which leads to high financial costs and resource-intensive operations. This high demand for requirements may prevent small companies from investing in their infrastructure and incorporating them into their software engineering workflow, unlike large tech companies that have the financial resources to integrate these technologies. Additionally, both the training and deployment of LLMs consume large amounts of energy, contributing to environmental impacts such as higher carbon emissions and greater energy usage.

- Black-box systems: A major issue with LLMs is that they are black-box systems, and access to these models is often only available through paid APIs provided by large tech companies like OpenAI and Google. Moreover, even with complete access to the models and their code, it is not possible to fully understand how they generate answers. This is because the complex operations performed by LLMs require sophisticated techniques to interpret their behavior.

- Security issues: Building LLMs on public code repositories is a potential hazard, given that if those errors exist in the training data as insecure practices such as hard-coded credentials and weak encryption methods, the models of LLM will mimic these vulnerabilities as well [23]. As explained earlier, LLMs are good at capturing patterns; consequently, if vulnerabilities are present in their training data, the models will learn representations based on them. This becomes an issue if developers use LLMs to write code, as the generated code may contain vulnerabilities and insecure practices.

Some technology experts, such as the CEO of NVIDIA, claim that programmers will no longer be necessary because LLMs will be capable of reaching AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) within a few years, possessing all the knowledge needed to replace us—especially in automated tasks like software programming. Although, many of the issues mentioned in the previous points are the challenges that LLMs must overcome before they can operate without human supervision. Moreover, since LLMs operate based on statistical patterns derived from data, it will be impossible to completely overcome these issues, though they can be mitigated using more sophisticated techniques. Therefore, human supervision from programmers and developers will still be required.

Conclusions

The emergence of LLMs, which are revolutionizing many fields such as research and the software industry, is the result of years of research and advancements in the field of NLP. The first language models were developed based on capturing statistical patterns in training data using Markovian assumptions. Later, neural networks were introduced to better encode these patterns and leverage this knowledge for other tasks, marking a paradigm shift with the advent of pre-trained models. Pre-trained models enabled the development of AI systems capable of retaining certain knowledge without needing to be trained from scratch. The arrival of the Transformer architecture allowed these models to be trained at scale, making better use of computational resources like GPUs and TPUs, giving rise to what we now know as LLMs.

Given the capabilities of LLMs to process and understand text, they have become useful tools in many fields, such as scientific writing and software engineering, even raising the question of whether these AI systems might replace humans in such tasks in the near future. On the one hand, LLMs help facilitate writing in English for researchers who are not native speakers, and can assist in the article review process by pointing out aspects a reviewer might overlook. However, LLMs face a number of challenges that must be overcome before they can replace researchers in these tasks. For example, while LLMs are good at mimicking patterns, they are not able to propose new research directions based on current gaps in the literature. On the other hand, in software engineering, LLMs are incredibly good at understanding coding problems and generating possible solutions. This capability allows LLMs to act as assistants that can generate documentation, suggest best coding practices, and refactor code according to the developer’s specifications. However, as with the case of scientific writing, when LLMs face unfamiliar or novel problems, they are often unable to solve them satisfactorily because such problems are not present in the data they were trained on. As a result, current LLMs are not capable of extrapolating complex solutions for new or unseen problems, unlike humans. Additionally, since LLMs learn patterns at a massive scale, they can absorb both good and bad practices. For example, they might learn poor programming habits or suggest inefficient algorithms for problems that require more optimized solutions.

Therefore, given the challenges of current LLMs, they are still far from replacing humans in scientific writing and software engineering. However, this does not mean that these models cannot help accelerate the automation of repetitive tasks, such as generating similar code or documentation. As a result, significant changes are expected in how researchers and developers carry out their work when equipped with these tools. Will they only bring good changes? It is hard to say. In the context of software engineering (or the industry in general), some job positions might no longer be needed. But for now, LLMs are still assistants, not researchers or developers.

References

[1] Muhammad Usman Hadi, Rizwan Qureshi, Abbas Shah, Muhammad Irfan, Anas Zafar, Muham- mad Bilal Shaikh, Naveed Akhtar, Jia Wu, Seyedali Mirjalili, et al. A survey on large language models: Applications, challenges, limitations, and practical usage. Authorea Preprints, 3, 2023.

[2] Chanlang Ki Bareh. A qualitative assessment of the accuracy of ai-llm in academic research. AI and Ethics, pages 1–20, 2025.

[3] Vassilka D Kirova, Cyril S Ku, Joseph R Laracy, and Thomas J Marlowe. Software engineering education must adapt and evolve for an llm environment. In Proceedings of the 55th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, pages 666–672, 2024.

[4] Atte Laakso, Kai-Kristian Kemell, and Jukka K Nurminen. Ethical issues in large language models: A systematic literature review. In CEUR Workshop Proceedings, volume 3901, pages 42–66. CEUR-WS, 2024.

[5] Michel Wermelinger. Using github copilot to solve simple programming problems. In Proceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1, pages 172–178, 2023.

[6] James Moor. The Turing test: the elusive standard of artificial intelligence, volume 30. Springer Science & Business Media, 2003.

[7] David M Berry. The limits of computation: Joseph weizenbaum and the eliza chatbot. Weizenbaum Journal of the Digital Society, 3(3), 2023.

[8] Claude E Shannon. Prediction and entropy of printed english. Bell system technical journal, 30(1):50– 64, 1951.

[9] Vivian Cook. Chomsky’s syntactic structures fifty years on. International Journal of Applied Lin- guistics, 17(1):120–131, 2007.

[10] Xiaoyong Liu and W Bruce Croft. Statistical language modeling for information retrieval. Annu. Rev. Inf. Sci. Technol., 39(1):1–31, 2005.

[11] Kun Jing and Jungang Xu. A survey on neural network language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.03591, 2019.

[12] Yoav Goldberg and Omer Levy. word2vec explained: deriving mikolov et al.’s negative-sampling word-embedding method. arXiv preprint arXiv:1402.3722, 2014.

[13] Tomas Mikolov, Martin Karafiát, Lukas Burget, Jan Cernock`y, and Sanjeev Khudanpur. Recurrent neural network based language model. In Interspeech, volume 2, pages 1045–1048. Makuhari, 2010.

[14] Matthew E. Peters, Mark Neumann, Mohit Iyyer, Matt Gardner, Christopher Clark, Kenton Lee, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Deep contextualized word representations. In Marilyn Walker, Heng Ji, and Amanda Stent, editors, Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long Papers), pages 2227–2237, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 2018. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[15] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

[16] Bonan Min, Hayley Ross, Elior Sulem, Amir Pouran Ben Veyseh, Thien Huu Nguyen, Oscar Sainz, Eneko Agirre, Ilana Heintz, and Dan Roth. Recent advances in natural language processing via large pre-trained language models: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 56(2):1–40, 2023.

[17] Gokul Yenduri, M Ramalingam, G Chemmalar Selvi, Y Supriya, Gautam Srivastava, Praveen Ku- mar Reddy Maddikunta, G Deepti Raj, Rutvij H Jhaveri, B Prabadevi, Weizheng Wang, et al. Gpt (generative pre-trained transformer)–a comprehensive review on enabling technologies, potential ap- plications, emerging challenges, and future directions. IEEE Access, 2024.

[18] Jason Wei, Yi Tay, Rishi Bommasani, Colin Raffel, Barret Zoph, Sebastian Borgeaud, Dani Yogatama, Maarten Bosma, Denny Zhou, Donald Metzler, et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682, 2022.

[19] Stefan Feuerriegel, Jochen Hartmann, Christian Janiesch, and Patrick Zschech. Generative ai. Busi- ness & Information Systems Engineering, 66(1):111–126, 2024.

[20] Weixin Liang, Zachary Izzo, Yaohui Zhang, Haley Lepp, Hancheng Cao, Xuandong Zhao, Lingjiao Chen, Haotian Ye, Sheng Liu, Zhi Huang, et al. Monitoring ai-modified content at scale: A case study on the impact of chatgpt on ai conference peer reviews. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07183, 2024.

[21] Weixin Liang, Yaohui Zhang, Zhengxuan Wu, Haley Lepp, Wenlong Ji, Xuandong Zhao, Hancheng Cao, Sheng Liu, Siyu He, Zhi Huang, et al. Mapping the increasing use of llms in scientific papers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.01268, 2024.

[22] Ruiyang Zhou, Lu Chen, and Kai Yu. Is llm a reliable reviewer? a comprehensive evaluation of llm on automatic paper reviewing tasks. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), pages 9340–9351, 2024.

[23] June Sallou, Thomas Durieux, and Annibale Panichella. Breaking the silence: the threats of using llms in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE 44th International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerging Results, pages 102–106, 2024.